Horror buffs, meet music nerds

A Q&A with the authors of ‘Blood on Black Wax,’ a new book about the best horror film soundtracks ever made.

With the right inspiration, an excellent soundtrack can elevate a horror film from comical to classic. It’s impossible to think about a movie like John Carpenter’s Halloween without recalling the foreboding theme music, which helped cement it as one of the most memorable horror films of all-time. At the same time, not every excellent soundtrack gets a movie it deserves; plenty of great music has been consigned to history’s bargain bin because it was unfortunately attached to one of the crappier Italian giallo films that nobody but film buffs remember. It’s all out there, in theory, waiting to be appreciated.

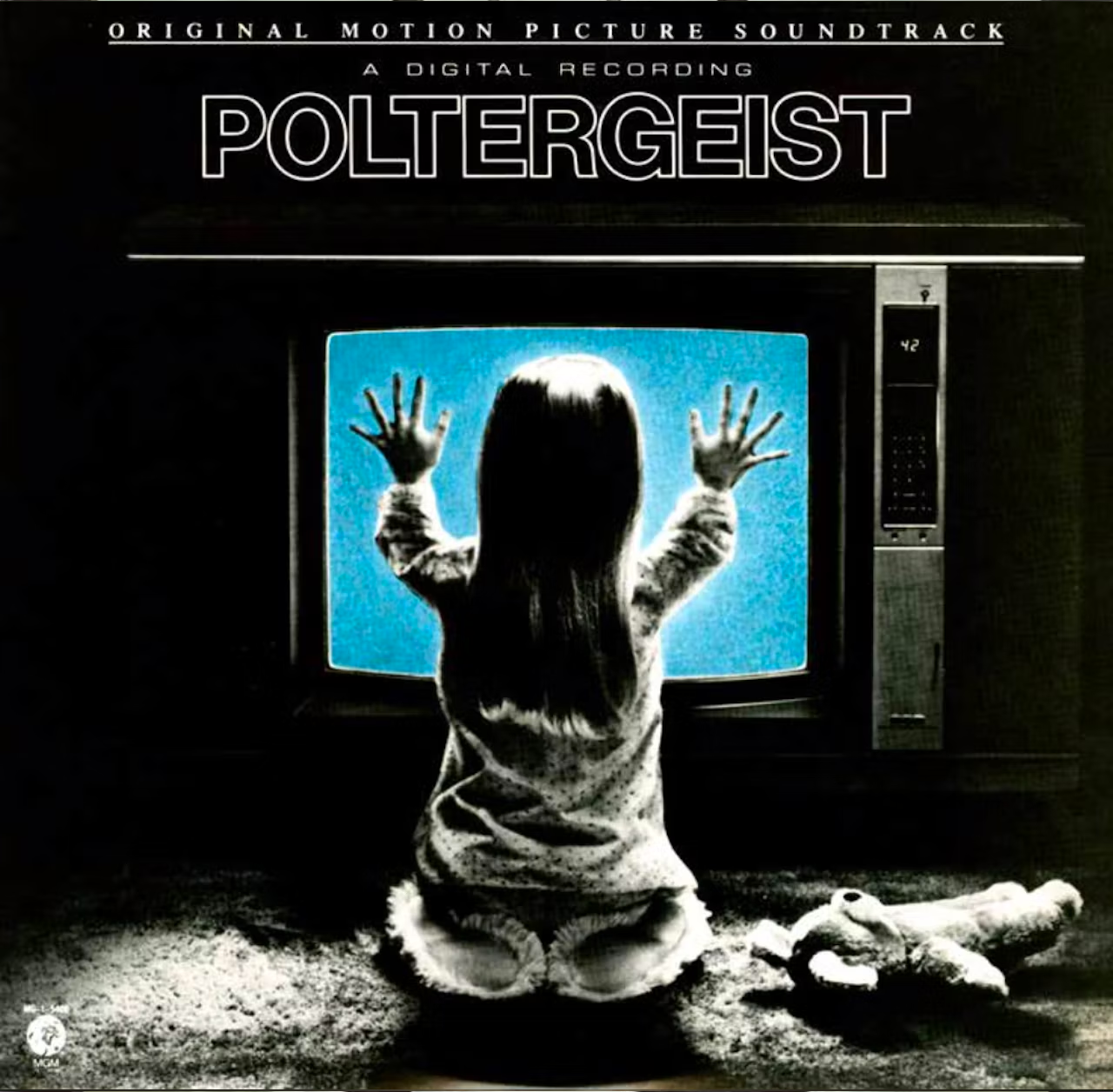

Reading Blood on Black Wax: Horror Soundtracks on Vinyl, a new book exploring classic horror soundtracks, feels like joining an impassioned conversation between authors Jeff Szpirglas and Aaron Lupton, as they lead readers through work that they’ve spent a lifetime cultivating a deep appreciation. Lupton is a librarian, record collector, and music editor for horror publication Rue Morgue, while Szpirglas is a school teacher and writer for Film Score, Rue Morgue, and other publications. The book is split up into seven subgenres including “Savage Science Fiction,” “Murder Maestros,” and “Rock 'N’ Roll Nightmares,” and cover a broadscope of anything from David Cronenberg’s Videodrome to Jaws. Often, some of the film score composers join in on the chat, such as Carpenter, Christopher Young (Hellraiser), and Mark Korven (The Witch), which makes the book even more integral for horror film fanatics.

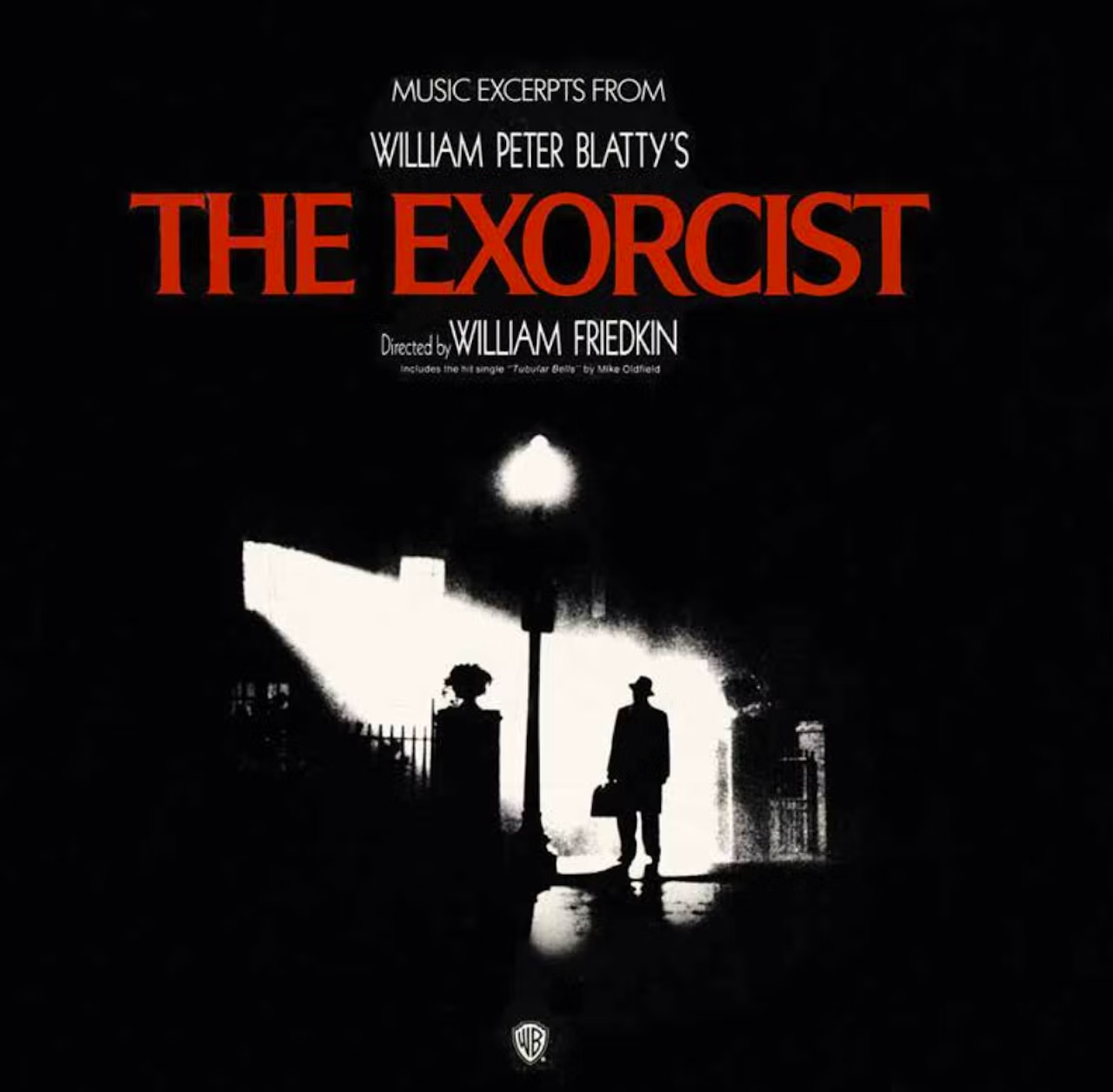

The one limiting factor: the score has to have been available on vinyl at one point or another. This isn’t a problem for Lupton, who has an enormous vinyl collection in his attic, and contributed almost all of the record cover images for the book. (The added visual factor of the 12 inch vinyl covers provides an illuminated understanding of the beauty of the described work.) In the book, the authors turn over some undercovered horror film history, like the decision to not include Lalo Schifrin’s initial score in the The Exorcist, while also incorporating the history of scores released on vinyl by labels like Waxwork, Death Waltz, and Sacred Bones. It’s all accessible and fascinating — not just for the record nerd or the horror fan, but for anyone who watched Hereditaryand found themselves thinking about the music afterwards.

Blood on Black Wax was initially released for Record Store Day this April, and released to a wider audience on May 13. Both authors spoke with The Outlineabout the book writing process, the films (even the bad ones) and scores included, and their personal fandom surrounding their new book.

Which horror film soundtrack started your fandom?

Aaron Lupton: I hate to be predictable but I think I’ll say John Carpenter and Halloween just because I have a specific memory of watching that film and being hit by the music harder than music normally hit me in horror films. I remember the whole ending of the film: Sam Loomis looking over the balcony and thinking, “Oh my God, what is going on? Michael Meyers really is the epitome of evil, the embodiment of evil.” And the way the music rolls over the credits, it was like.. wow. For me, today, I would still say that John Carpenter is my favorite horror composer.

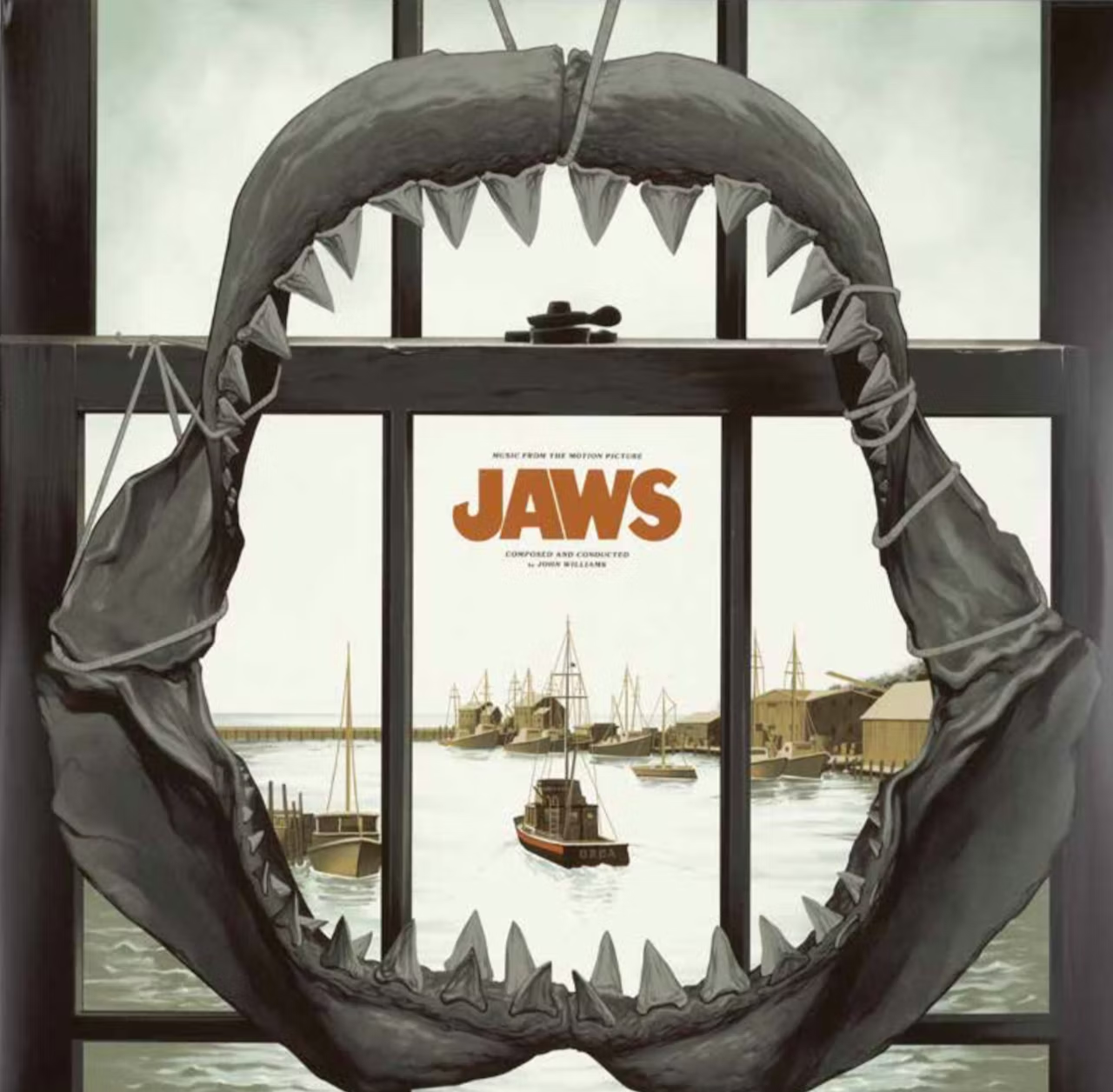

Jeff Szpirglas: I keep coming back to Jaws — probably because, like Halloween, they’re both based around these very iconic ostinatos that loop and repeat and kind of get into your subconscious. Clips of Jaws would always show up on TV. Whenever PBS would be doing a special on John Williams, I would always be drawn to the Star Wars clip and the ET clip that they would have of his music, and then they would show these guys on a boat with a dorsal fin popping out of the water. That theme just hit me in the guts. I remember for years later just wanting to see Jaws and not being allowed to see it, and then finally having the crap scared out of me when I did.

You guys both used the visual element to describe what initially got you interested in horror soundtracks. What gives horror soundtracks the ability to stand apart from the film?

JS: Coming into this project, for me at any rate, there were films that I definitely knew and there were films that I got assigned to or didn’t know the movie as well or know the music as well. It's a bit of a shift because when I'm reviewing Jaws, I'm thinking about the movie and I'm thinking about the music and I'm thinking about the music in context with the film. It is hard to separate them.

Soundtrack listening as a kid growing up was always a way to re-experience the movie before you could see it on video because media wasn’t nearly as instantaneous as it is today. So the soundtrack becomes this little vestibule to re-experience the movie in a different way or to hear the sound of it in a different context. There are definitely movies in the book where I didn’t have the same context of knowing the film intimately and it sometimes is an interesting experience to try to listen to the soundtrack on its own terms because it was never meant to be listened to independently. Sometimes they really work well on their own — they take you down this very dark and interesting trail — and sometimes they can be a chore to listen to because they might be really repetitive. Halloween is a repetitive soundtrack; that theme gets used in a pretty substantial way in the soundtrack and in the movie. But if you listen to it divorced from the film, that Halloween soundtrack plays about five times, and you’re constantly going, "why do we keep hearing that Halloween theme?" But in the movie, it works wonders.

YouTube

AL: For example, I think of John Harrison’s Creepshow. If you listen to it divorced from the film, there are so many parts of that soundtrack that don’t sound like they would ever have been intended to be used in a horror film at all. You maybe start to realize different aspects of the film that exist. There are soundtracks that, if you listen to them independently of the film, they work really great. John Carpenter has this second career as a rockstar because his scores sound really great live — Christine, Escape from New York, it's almost like listening to a rock album — whereas something like Hereditary or The Babadook as two recent examples, they’re hard to listen to independent from the film. But at the same time, I think that there's this correlation between how much you love a film, and how much you love its soundtrack. If you absolutely obsess over a particular title then you're going to put on that soundtrack and crank it to eleven and obsess over it.

Added to that, you guys include a couple objectively bad movies with great soundtracks. Do you mind talking about one or two of those?

AL: I don’t know if you watch Joe Bob Briggs' show on Shutter, but it’s become my weekly ritual to sit down with the family and watch Joe Bob Briggs on Friday night. He unfortunately brought up [1980 Italian sci-fi horror film] Contamination on last week’s episode. — and I say unfortunate, because as a new father I’m on very limited sleep, and so it’s kind of like, your movie choices are very critical. Contamination is a boring and bad movie, but it has one of the great Goblin [Italian band renowned for their film music] soundtracks. Contamination is obviously not mentioned in the same breath as Suspiria and Deep Red because those two are colorful bright films that are celebrated as works of art, and Contamination is not. It has a great soundtrack that gets hindered by its visuals, but it works great as a record.

JS: It only became a soundtrack because the movie had such a cult surrounding it, but we profiled Manos: The Hands of Fate. I know it through Mystery Science Theater, where I saw it when I was in high school. I was always amazed at the cult that surrounded it. Somebody actually dug up the 35 mm film prints and cleaned them up and gave it a legitimate release, and they did a really good job making the soundtrack to Manos that no one in their right mind would ever put on a record, but it’s actually got great art. There are two surprisingly listenable songs by Nicki Mathis, and we tracked her down. She didn't have too much to say other than that she totally disliked the movie, she couldn’t believe it got released, but people ask her to keep singing those songs — a little feather in her cap.

YouTube

When you all set out on this project were there any soundtracks you knew you had to include from the start?

AL: So many of the classic horror films came out in the ’70s and early ’80s when vinyl was still a dominant medium for music, so we were going to capture The Exorcist and Jaws and Halloween. Those ones were kind of no-brainers, though; they weren’t ones that we necessarily got really excited about. I think that it was more about stuff like [1985’s] Fright Night as a compilation album or [1985’s] Return of the Living Dead… I have so any personal favorites in there I don’t even know where to begin. [1988’s] The Serpent and the Rainbow is one, just because it’s such a cool score that no one really talks about that you get to highlight and be a fan and share your excitement over.

JS: I definitely wanted to push for having a few pages about hammer horror and celebrating James Bernard who is such a great composer. In some cases, there is an era where we flipped from vinyl to CD. I'm definitely a collector of CDs, so to make it fit the book it had to exist on vinyl in some form at some time. The good news was that Aaron's record collection is so intense that we often had it or Aaron was able to somehow wrangle a copy of something so we could put it in the book. Good job, Aaron.

Aaron, do you own all of these records?

AL: There were a few that we had to track down at the final hour. The good thing is that since the whole vinyl resurgence has happened there is this community of collectors that has grown up around it as well as people that are into synthwave. They tend to be part of the same audience, so I was able to draw on some of those people. For example, a collector in New Jersey was able to give us a couple of images, like the [1981’s] Inseminoid LP. I don’t own that, and it's really expensive these days to track down. I would say that over 90 percent of it is mine, for sure.

JS: There were many nights scanning in Aaron's albums using 600 dpi just waiting for this massive scanner to chug away and give the images life.

What do you think sets horror soundtracks apart from other film soundtracks?

JS: Christopher Young, in his afterword in the book, talks about how liberating it can be to write for a horror score because you kind of lift all the rules. You don't necessarily need to adhere to tonality that a mainstream movie or a comedy or a drama does. Those aren't necessarily trying to unnerve you, and they tend to rely on traditional sounds. Maybe it's synth, maybe it's orchestral. In a horror film, there are no rules. The Exorcist, I remember talking about the guy who did the sound mix and to get the snapping of the vertebrae in Regan's neck — coming up with the sounds just for that, I think he took a wallet with credit cards and flicked it, and it got that clicking sound. That extends to the music as well. In a lot of these horror films, where sound design ends and where music begins is a lot more fluid than in other genres. I think it gives the composer a lot of free reign to experiment, as well as the filmmakers. They aren't always the easiest things to listen to, but they're never dull because they are based around trying to be progressive and experimental.

AL: I think that the reason that there’s so much interest in horror soundtracks as opposed to other genres is pretty much parallel to people's interest in horror as a film genre. I always say that horror fans are a little different from fans of action films or even sci-fi films. Horror fans obsess over the movies. They want to know everything about the movie; they want to own everything by the movie. They want to own a DVD and a Blu-Ray and they want a library of horror films and they want to wear their film's t-shirt and they want to get tattoos of their favorite horror film. They just have to go deeper and deeper and deeper.

Of course, part of the aesthetic of a film is its music. If you can even own a copy of the music that's in the film and study it and get into that, then you've gone even deeper. Say for example, a movie like Alien with the score by Jerry Goldsmith, which is considered this huge classic and then within this sci-fi horror genre you might have a movie like Forbidden World, which is really low budget and would not be considered a great film by any stretch of the imagination, other than it’s entertaining and it has a really lo-fi synth soundtrack. If you love that movie, regardless of whether it’s good or bad, then part of what makes that movie amazing is the music tapestry that helped create the aesthetic that made it so appealing, whether it’s a lo-fi synth score or a huge grand orchestra. People tend to be fans of horror in a very different way than they’re a fan of comedies and stuff.

YouTube

For whatever reason, whether it’s the obsessive fandoms or other associations, metal music and horror are always linked. But something that surprised me about your book was how often jazz came up. Classic horror films like Friday the 13th, Rosemary’s Baby, and the 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body-Snatchers, among others, all include some jazz influence. Why do you think that is?

JS: I don’t think I’ve considered that until now, but I think you’re right. I think even Joe LoDuca, who did The Evil Dead score, he was a jazz musician as well. I wonder if that does speak to improvisation and the freedom to experiment and create. Joe LoDuca didn’t set out to do horror scores, he was a jazz musician, but he got the gig. I do wonder though, if there could be a correlation between that type of mindset, where you’re improvising and making things up and experimenting. It does make sense to me that that would translate really well to a horror score where you’re probably trying to push the envelope to try something new.

AL: I was aware that there were a lot of jazz horror scores, and whenever I think jazz I think of Martin and, of course, Rosemary’s Baby. I think it’s just part of that film. In the case of Martin, jazz evokes this imagery of smoky nightclubs, and that was a part of rebellious culture at the time. That’s what that movie was, a modern take on the vampire story. The same thing with Rosemary’s Baby, that movie really was a shocking film for its time and you could say rebellious film for its time. It was evocative of that particular era. Of course, they had a master working at the helm on that film, Krzysztof Komeda.

What made you decide to include interviews with composers rather than just write about the film yourselves?

AL: We wanted to get to talk with these guys.

JS: Yeah, it was pretty cool to get a 45 minute phoner with John Carpenter to kick off the book.

AL: I think that we really approached this as a passion project, so if it’s something you’re passionate about, you’re like, "Hey, let’s try to get an interview with John Carpenter” and we got some dream interviews out of it. We can sit here and theorize about all these topics that we’re talking about — about why people like horror soundtracks or why they work or how they work, but you aren’t going to know the answers to those questions unless you go to the source and do the interviews.

JS: Sometimes there were just really interesting stories and they could provide context for something. We ended up getting Lalo Schifrin to talk about The Exorcist. We put the questions together and Aaron did the interview and Aaron was told to not mention The Exorcist, so we made it about The Amityville Horror.

YouTube

AL: The guy is like 80 years old. We’re probably never going to interview him again, so the worst thing that could happen is he’s going to hang up on us. So I asked him why his score of The Exorcist was unused. [Schifrin composed a soundtrack for The Exorcist that was only played in a trailer for the film, and was eventually replaced by disparate music from various composers] He gave me a great quote — that the music he composed was so ugly and so upsetting that people were vomiting in the theater.

JS: I think as someone who would want to buy the book in the store, it’s fun to work on a book that you would want to go and buy yourself. That would be something I would be looking for, having space devoted to interviews whenever we could gave it an extra something for a fan wanting to pick it up and have something fresh and new.

Link at the Outline